Tim Side, CFA® – Investment Strategist

“From thirty years as a practicing historian, I have come to the conclusion that there is but one, singular, lesson of history. It is this — there are no permanent winners or losers.”

-Ramachandra Guha[1]

The current environment is rife with uncertainty. Following two seismic events, the COVID-19 pandemic and the first ground war in Europe since World War II, investors have also had to grapple with the most rapid rate hiking cycle from the Federal Reserve since 1980, deteriorating relations between the United States and China, the two largest economies in the world, a downgrade in the credit rating of the U.S., the country behind the global reserve currency, and a war in the Middle East. As we enter 2024, a major election year for many countries around the world, the heightened geopolitical consternation appears poised to continue.

This is our second part of a three-part series designed to provide some context and insights into the current macroeconomic environment:

- Part 1: Where are we now? A review of the current geopolitical environment to determine whether things are different today and to help set the stage for an understanding of how geopolitics affects markets.

- Part 2: Where are we going? A review of long-term trends potentially forming.

- Part 3: What should we do? A practical guide on how to invest around geopolitical uncertainty.

Part 2: Where are we going?

Every year, our team formally reviews more than a dozen annual investment outlooks from asset management firms that we know and respect to generate a rough “consensus” view of where the markets may be going in the year ahead – and right now we are in the heart of 2024 outlook season. Not only is this exercise helpful to get a sense of what the industry’s brightest minds are looking ahead to, but it also provides a checkpoint for how the previous year’s consensus expectations panned out and a reminder that prognostication should be taken with a grain of salt.

For example, five of the 12 outlooks reviewed last year called for a recession in 2023, while only two accurately predicted that the U.S. would avoid recession.

So, with the dangers of predictions in mind and recalling the current macro environment we discussed in Part 1, there are four key aspects of the shifting world order that we think may provide some insights into where things could go: inflation and higher rates, a reshaping of political alliances, a focus on energy security, and fears of the U.S.’s global leadership declining.

Inflation and Higher Rates

In the first part of this series, we discussed how the shifting world order has pushed countries and companies to create more resilient supply chains through friendlier, or least more politically reliable, entities. Intuitively, moving away from the cheapest and most efficient manufacturing sources (such as China) should mean higher prices going forward, though putting hard numbers on the impact of switching supply lines is difficult, if for no other reason than inflation targets are closely monitored by central banks, which then try to enact polices that could counter upward pricing pressure.

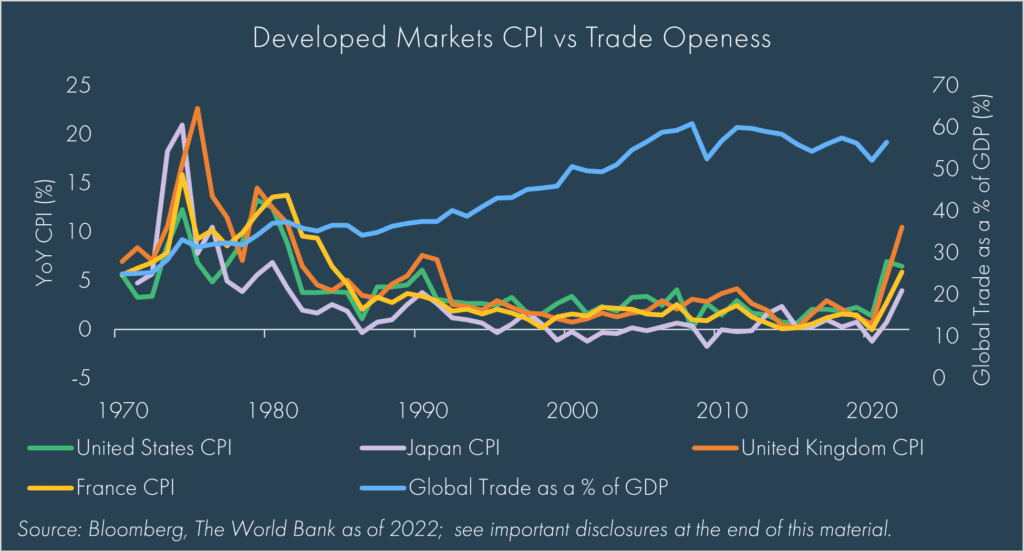

While correlation does not equal causation, there has generally been an inverse relationship between trade openness and inflation for developed markets.[2]

This dynamic can be seen in the drastic price declines of certain goods, such as toys and televisions, over the last several decades – free trade made it easier to export manufacturing to markets with cheaper labor and other input costs, which resulted in ever-lower prices for consumers. In contrast, more service-oriented segments, such as medical care and college tuition, saw a significant rise in prices, partially due to the inability to outsource supply-production to cheaper labor markets.[3]

So, as companies build more resilient supply chains away from the most efficient manufacturing sources — i.e., restricting trade — there is a necessary increase in costs. Fortunately for consumer’s wallets, not all efficiency is lost, as alternative manufacturing countries like Vietnam, Mexico, and Poland still offer cheaper manufacturing bases relative to more developed nations. However, even if these new manufacturing sources only cause prices to rise modestly, it could have a significant impact on interest rates.

As we know, inflation spiked to multi-decade highs after the COVID-19 pandemic. Central banks hiked interest rates quickly and dramatically to combat surging prices, a policy that appears to be effective, as evidenced by falling inflation rates around the world. Now the introduction of new, more expensive supply chains could complicate central banks’ mission to return inflation to target levels by reinforcing higher consumer prices, potentially forcing central banks to keep rates above the near-zero level markets have become accustomed to over the past decade to achieve their inflation targets. While market expectations for rates are lower in 2024, a view confirmed by the Federal Reserve’s estimates during the week of 12/13/2023, the long-term expectation for rates is generally higher than the last decade on average.

Reshaping of Political Alliances

The era of Hyper-Globalization from 1990 to 2008[4] completely reshaped the global economy, and few, if any, countries benefitted more from open trade than China.

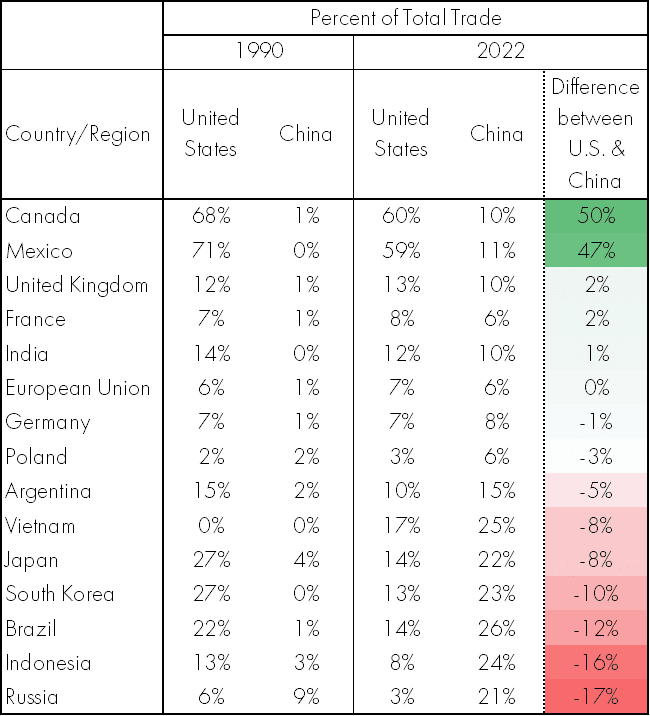

The table below highlights the monumental shift in trading relations by comparing the percent of total trade that certain countries had with the U.S. and China in 1990[5] to 2022 levels.

While China’s rapid integration in the global economy is a prominent takeaway from this table, it should also be noted that both the U.S. and China remain intertwined with most of these countries from a trade standpoint. For example, even though countries such as Vietnam, Japan, South Korea, and Brazil now rely more heavily on trade with China, they still maintain significant trade balances with the U.S. Additionally, virtually all global trade partners benefit heavily from the presence of U.S. military keeping shipping lanes secure and open.

While this dynamic remains one of the significant incentives to maintain some semblance of the previous world order, the world is shifting nonetheless and new regional trade blocs appear to be forming.[6] As noted in Part 1, many of the trade tariffs enacted during Donald Trump’s presidency remain in place, and the World Trade Organization saw the single largest number of new regional trade agreements (RTA) in a given year (66 total) in 2021.[7]

A notable change in the new RTAs over the last decade or so has been an increase in plurilateral agreements (rather than bilateral). This includes the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (Asia-Pacific – 2018), Pacific Alliance (Latin America – 2011), the African Continental Free Trade Area (Africa – 2019), and the United-States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (North America – 2020). While each agreement brings its own unique features, the broad theme of the pacts highlight the push towards nearshoring and friendshoring.

Increased Focus on Energy Security

No analysis on geopolitics would be complete without discussing energy.

Renewable energy sources continue to take more of the global energy market share, though fossil fuels (oil, gas, and coal) remain the dominant source of energy, making up 82% of the global energy mix according to the UK-based Energy Institute.[8] This is down from 85% five years ago, highlighting both the progress made and the long road ahead.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine forced many countries, most notably Germany, who imported more than 30% of their gas from Russia,[9] to toss out their previous playbook and rethink energy supply and sources. In some ways Russia’s action provided further motivation for countries to diversify energy sources, but it also highlighted just how reliant the global economy still is on fossil fuels – and countries like India and China have benefitted from buying cheaper Russian oil.[10]

By all indications, the push towards lower carbon emissions seems to have global support, as evidenced by nearly 200 countries agreeing to begin reducing global consumption of fossil fuels at the COP28 Climate summit.[11] However, the willingness and practical extent to which countries can align themselves with this goal varies widely. One needs to look no further than China for an example: The Chinese are the global leader in building renewable energy sources, but they also rely heavily on coal to meet energy demands.[12]

The Potential Decline of U.S. Dominance

The global dominance of the United States is striking: The U.S. boasts the world’s largest economy by GDP, fields the world’s largest military, sports the world’s deepest and most liquid capital markets, and it is a net oil exporter – four massive advantages that only scratch the surface of U.S. leadership.[13]

In 2023, the U.S. saw a credit rating downgrade, debt default concerns, and waning political support for military spending. Given these dynamics, and with global isolationism growing in popularity within some political factions, it is only natural that the dominance of the U.S. would come into question.

We wrote a piece back in April regarding concerns over the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status (Link Here), and concluded with the following statement:

Will the dollar be replaced? It is very unlikely to happen in our lifetimes, but sometime in the distant future, it is certainly quite possible. When and how fast would the global financial markets diversify meaningfully away from it are other questions that go far beyond anyone’s ability to predict.

This statement seems to fit well as we think about the concerns over the U.S.’s global hegemon status. We believe the economic principle of “people respond to incentives” still holds, and there are still significant incentives for countries to stay aligned with the U.S.’s general policies and expectations. However, the U.S. is not the only game in town as an economic and military partner, and over time, the incentives may change for certain countries. The speed and magnitude of any change in dominance goes beyond our ability to forecast, but it should be remembered that it took a world war to dethrone the previous global reserve currency. Absent a cataclysmic event, it is unlikely that the U.S. will be dethroned any time soon.

Part 2 Conclusion

Parts 1 and 2 of this series sought to lay the groundwork for where we are and where we might be headed. While they offer little in the way of direct investment application, we hope the comments provide better insight into how the market is currently thinking about some of the current geopolitical events.

Predicting where we are going is, at best, an educated guess, and even the best and brightest minds often fail to get macro calls right. At Moneta, you can rest assured that the success of your portfolio is not reliant on specific outcomes stemming from any of these broad issues. We build portfolios thoughtfully and carefully, always considering what is best for your needs.

The next, and final part will aim to provide some practical insights on how to think about these risks in one’s investment portfolio.

DISCLOSURES

© 2023 Advisory services offered by Moneta Group Investment Advisors, LLC, (“MGIA”) an investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). MGIA is a wholly owned subsidiary of Moneta Group, LLC. Registration as an investment adviser does not imply a certain level of skill or training. The information contained herein is for informational purposes only, is not intended to be comprehensive or exclusive, and is based on materials deemed reliable, but the accuracy of which has not been verified.

Trademarks and copyrights of materials referenced herein are the property of their respective owners. Index returns reflect total return, assuming reinvestment of dividends and interest. The returns do not reflect the effect of taxes and/or fees that an investor would incur. Examples contained herein are for illustrative purposes only based on generic assumptions. Given the dynamic nature of the subject matter and the environment in which this communication was written, the information contained herein is subject to change. This is not an offer to sell or buy securities, nor does it represent any specific recommendation. You should consult with an appropriately credentialed professional before making any financial, investment, tax or legal decision. An index is an unmanaged portfolio of specified securities and does not reflect any initial or ongoing expenses nor can it be invested in directly. Past performance is not indicative of future returns. All investments are subject to a risk of loss. Diversification and strategic asset allocation do not assure profit or protect against loss in declining markets. These materials do not take into consideration your personal circumstances, financial or otherwise.

DEFINITIONS

Trade (% of GDP): Trade is the sum of exports and imports of goods and services measured as a share of gross domestic product. Source: World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files.

US CPI: This CPI represents changes in prices of all goods and services purchased for consumption by urban households. User fees (such as water and sewer services) and sales and excise taxes paid by the consumer are also included.

Japan CPI, UK CPI, and France CPI: Consumer Prices (CPI) are a measure of prices paid by consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services. The yearly (or monthly) growth rates represent the inflation rate.

Total trade equals total imports plus exports.

[1] https://ramachandraguha.in/archives/the-only-lesson-that-history-can-teach-us-hindustan-times.html

[2] From 1970 to 2021, inflation for the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, and France had an average correlation to global trade as a percentage of GDP of -0.60.

[3] https://howmuch.net/articles/price-changes-in-usa-in-past-20-years

[4] https://www.piie.com/publications/working-papers/hyperglobalization-trade-and-its-future

[5] Russian trade estimates as of 1992.

[6] https://www.confluenceinvestment.com/weekly-geopolitical-report-parsing-the-worlds-new-geopolitical-blocs-may-9-2022/

[7] https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/region_e.htm#facts

[8] https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/062623-fossil-fuels-stubbornly-dominating-global-energy-despite-surge-in-renewables-energy-institute

[9] https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/how-dependent-is-germany-russian-gas-2022-03-08/

[10] https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/russian-oil-shaves-indias-import-costs-by-about-27-bln-2023-11-08/

[11] https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/countries-push-cop28-deal-fossil-fuels-talks-spill-into-overtime-2023-12-12/

[12] https://www.cnbc.com/2023/03/08/energy-chinas-renewables-progress-comes-alongside-a-coal-power-boom.html

[13] https://www.economist.com/briefing/2023/04/13/from-strength-to-strength