Kevin Ward – Advisor

Einstein is often credited—perhaps apocryphally—with identifying compound interest as the world’s eighth wonder. Benjamin Franklin was also famous for his comments on the power of money compounding: “Money makes money. And the money that money makes, makes money.” But he did more than just comment—he put his money where his mouth was (NYT, subscription publication), bequeathing upon his death in 1790 the rough equivalent of $4,400 each to Philadelphia and Boston with the caveat that the money was to be invested and not touched for at least 100 years, at which time roughly 75% could be withdrawn. The remainder was to wait another 100 years. The result in 1990 was some $2 million for Philadelphia and over $5 million for Boston (the two cities managed their investments differently; hence the different ending balances)—all from just letting the money sit and earn some 5% annual interest or so.

Books have been written on the topics of personal finance and the power of compounding—neither is a new concept. But the importance of saving early and often can hardly be overstated—particularly for those interested in building financially independent lives. Whatever your current age—whether you’re in high school, a new college graduate, or whether you’re in your 30s or 40s—you can start saving now. Building good habits early will mean a few things: First, once you start earning more and are faced with the temptation of fulfilling your childhood dream of owning a sports car or a boat or a luxury watch, your muscle memory is likelier to kick in, and you’ll save instead of splurge (or at least you’ll save then splurge). Second, your delayed gratification habit will mean you’re able to fulfill those dreams sooner than others who don’t develop solid financial hygiene early in their lives.

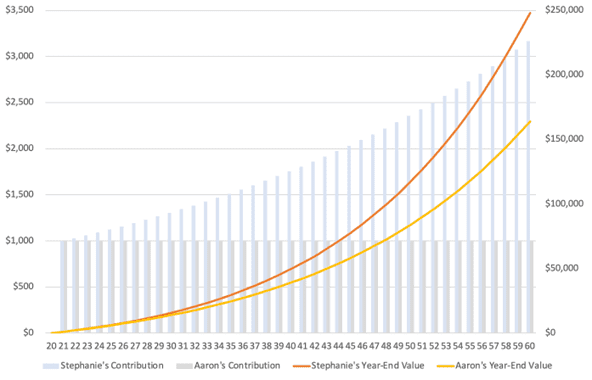

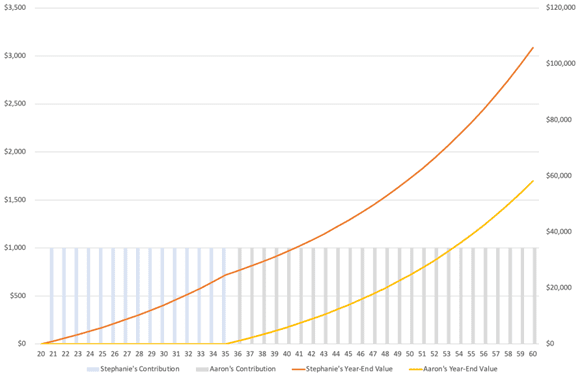

But enough theory—what do the numbers look like? Exhibits 1 – 5 show the outcomes of five scenarios for hypothetical savers Stephanie and Aaron. In the first scenario, Stephanie and Aaron (who are the same age and in the same financial situation for each scenario) begin saving $1,000 monthly at age 21 invested at a 6% annual compound rate. Stephanie increases her savings amount by 3% annually, while Aaron sticks with $1,000 annually.

Exhibit 1: Stephanie Increases Her Savings, Aaron Doesn’t

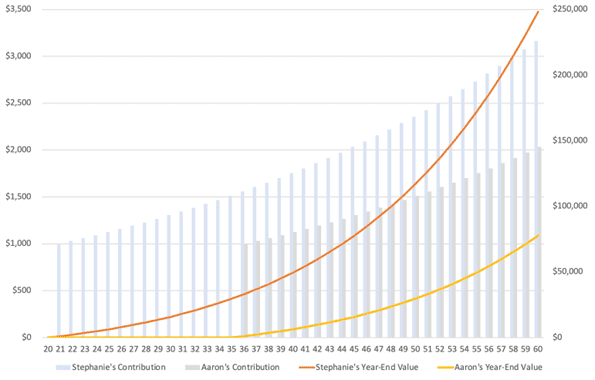

Stephanie behaves the same way in scenario two, but Aaron delays his savings efforts until age 36, which he similarly increases 3% annually. As Exhibit 2 shows, Aaron’s delayed start meaningfully diminishes his saved amount by the time he’s 60.

Exhibit 2: Aaron Delays His Start

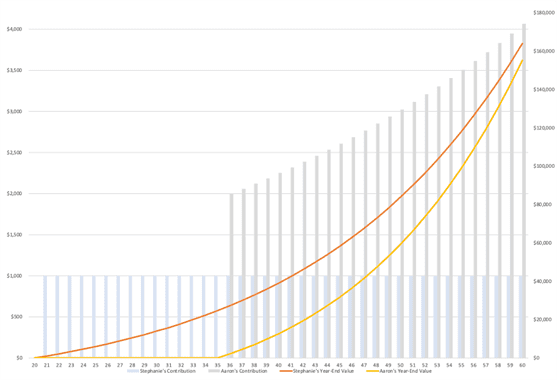

In the third scenario, Stephanie starts saving $1,000 annually for the first 15 years but then stops—though her initial savings continue compounding at 6% annually. Aaron, in contrast, delays his start for 15 years but then saves $1,000 annually, also compounding at 6%. Interestingly, even though Aaron ends up saving for more years than Stephanie (25 versus 15), Stephanie’s early start allows her to benefit from a longer compounding period, and she still winds up with a higher ending balance.

Exhibit 3: Stephanie Stops Early, Aaron Starts Late

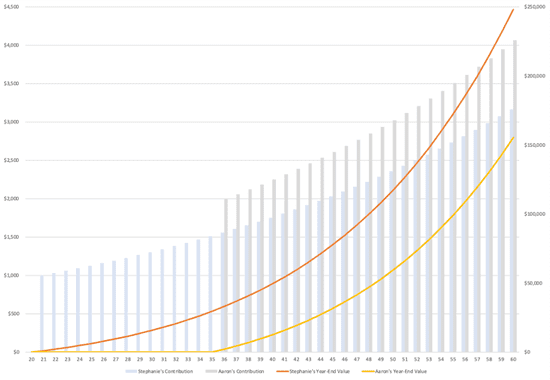

Finally, in the fourth and fifth scenarios, Stephanie saves $1,000 annually, while Aaron saves $2,000 but waits to start saving until age 36. Even with a savings rate twice Stephanie’s and increasing his rate 3% annually, Aaron’s ending value fails to match hers. If Stephanie manages to similarly increase her savings by a modest 3% annually (scenario five), the effect on her ending value is even more striking (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 4: Aaron’s Rate Doubles Stephanie’s, but He Waits to Start

Exhibit 5: Stephanie Increases Her Annual Savings, Aaron Starts Late at a Higher Rate

These are just five hypothetical examples—there are an infinite number of ways to game out possibilities. But whatever the scenario, the conclusion is largely the same: Saving early and saving as much as possible allow for powerful compounding over time.

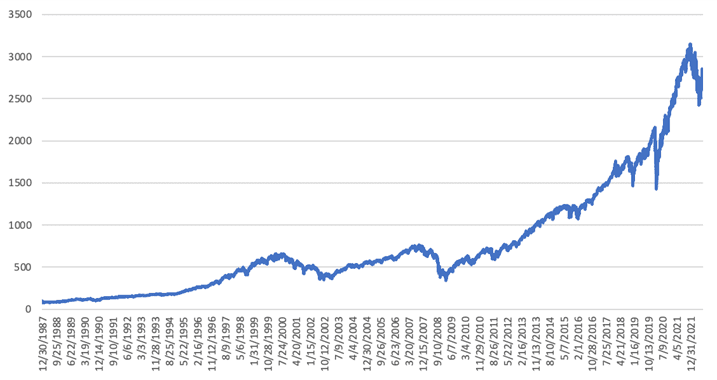

Obviously, a key variable in these calculations is the rate of return. We’ve used a relatively modest, but achievable, 6%—which is lower than the S&P 500’s long-term average annual return of almost 12%. But even 6% can be hard to achieve for individual investors going it alone. Why? Left to our own devices, we’re likelier to fall prey to some common behavioral errors.

One of the classic traps is the temptation to trying to time the market—either waiting for a market dip or selling at what you think is a high. The unfortunate reality is this approach often achieves the opposite of the intended aim—buying high and selling low. Or you miss the up days altogether. Part of the key to achieving even close to long-term average returns is being invested far more often than you’re not. Since the market’s average is achieved by relatively volatile individual days, and since we’ve not perfected our crystal ball just yet, it’s impossible to know whether any given day will be one of the big up days that helps balance out the down days. Though it might be tempting to try to avert the down and just catch the up, countless studies show it’s all but impossible.

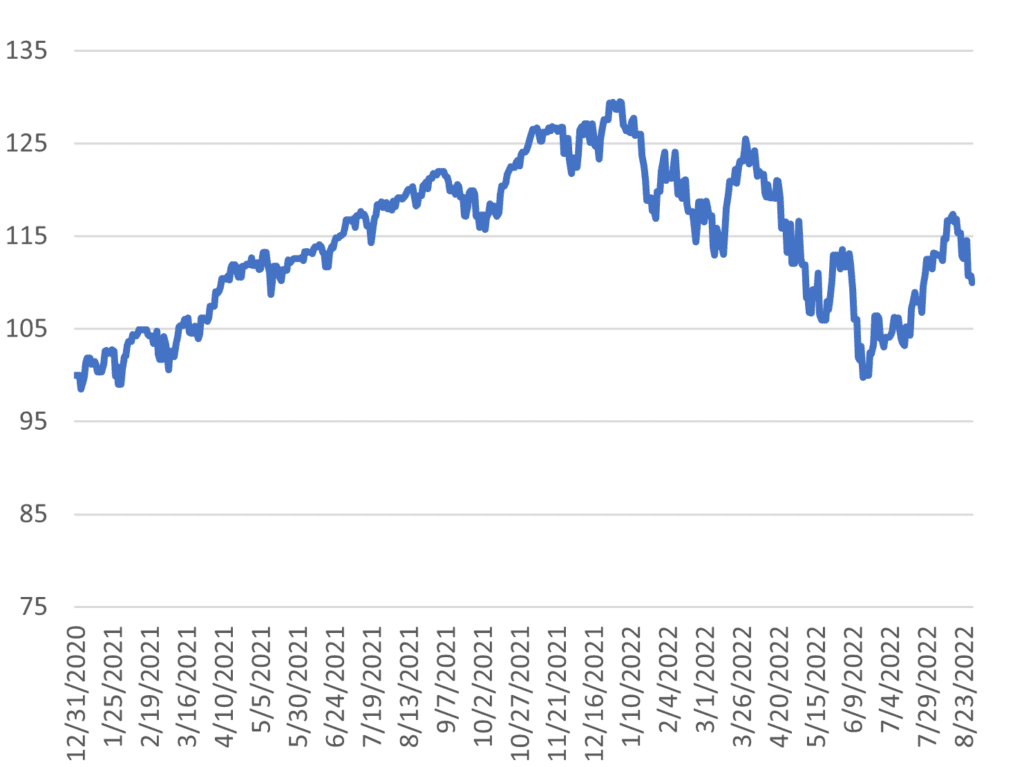

One of the keys is maintaining a long-term perspective—see Exhibit 4, which shows the S&P 500 Index’s long-term total returns. But then consider Exhibit 5, which shows the total return over just the course of 12/31/2020 to 8/29/2022. It’s challenging amid days like some of those in 2021 and 2022 to remember that in the long run, those days are likely to smooth into something resembling Exhibit 4 (though returns are never guaranteed, naturally). The down days can be considered the price for the up, but most individuals just aren’t individually wired to tolerate them.

Exhibit 4: S&P 500 Total Return Index, December 31, 1987 – August 29, 2022 Indexed to 100 as of December 31, 1987

Exhibit 5: S&P Total Return Index, December 31, 2020 – August 29, 2022 Indexed to 100 as of December 31, 2020

So how do you set yourself up for long-term financial success? As we’ve attempted to show, one key is just starting—start saving and start investing. Timing doesn’t particularly matter—i.e., it’s not advisable to wait for a pull-back, since they’re devilishly hard, if not impossible, to time, and in the long run, remember what you want your zoomed-out chart to look like. Whether you catch this or that side of any market “Vs” won’t ultimately matter much to your long-term outcome.

The next question is how to invest—and in what. This is where a financial advisor can be a tremendous resource. Not only will an experienced one advise you well on your investments, but they can also help you do the math on where you are and where you want to be and develop a well-constructed plan devised to get you there. Perhaps most importantly: They can keep you from becoming your own worst enemy, succumbing to all the temptations that have plagued investors since flower-arranging was all the rage in the Netherlands.

Why can’t you just wait a few years until you’re better positioned—maybe just until you have that new car, or until you can buy the engagement ring or the house or, or, or? As you get older, the amounts required to catch up increase. Quickly. (Revisit Exhibits 2 through 5, showing where Aaron ends up when he waits until age 36 to start saving.) Which means the future cost of today’s instant gratification is incredibly high. You’re better off saving what you can, when you can, while still allowing for those important purchases along the way (we have a whole series on how to think about your personal finances during various phases of life)—this increases the likelihood you wind up like Stephanie instead of Aaron.

We’re not reinventing the wheel with any of these ideas, but the fact that there’s still cause to write such a piece making a case for compounding and saving—that the issue isn’t considered long-since settled—means many are either unaware of, unwilling to do, or incapable of doing what it takes to get there. So what about you? Will you defy the odds? Or will you opt for financial uncertainty down the road, when you’d rather be figuring out where you’d like to retire and which destination you’d like to visit next year? Our hope is you will choose the road less traveled.

© 2022 Moneta Group Investment Advisors, LLC. All rights reserved. The information contained herein is for informational purposes only, is not intended to be comprehensive or exclusive, and is based on materials deemed reliable, but the accuracy of which has not been verified. Examples contained herein are for illustrative purposes only based on generic assumptions. Given the dynamic nature of the subject matter and the environment in which this communication was written, the information and opinions contained herein are subject to change. This is not an offer to sell or buy securities, nor does it represent any specific recommendation. You should consult with an appropriately credentialed professional before making any financial, investment, tax or legal decision. Past performance is not indicative of future returns. All investments are subject to a risk of loss. Diversification and strategic asset allocation do not assure profit or protect against loss in declining markets. These materials do not take into consideration your personal circumstances, financial or otherwise. An index is an unmanaged portfolio of specified securities and does not reflect any initial or ongoing expenses nor can it be invested in directly. Exposure to an asset class represented by an index may be available through investable instruments based on that index.