Click here to download the PDF version of this piece.

The ongoing debate between active and passive1 investing continues as passively managed funds have seen net assets swell by an average annual rate of 11.9% from 2000 to 2022, far greater than the 4.7% growth rate seen in actively managed fund net assets2. Passive investing – commonly used to describe buying a fund that tracks a market index – has increased in popularity over the past few decades, mainly because passive funds typically charge lower fees than actively managed funds. Proponents of passive investing argue that active managers cannot routinely outperform the indexes they track, especially net of fees. Furthermore, they argue many markets are highly efficient, removing the potential to regularly identify and exploit mispriced securities. On the other side of the coin, proponents of active management argue that it can provide value in more than one way: the potential to achieve a higher return than the benchmark in up-markets, the agility of active management which can help protect the investor’s capital through defensive moves in down-markets, or attractive risk-adjusted returns when compared to some passive funds. Thus, as its proponents argue, actively managed funds can be a practical solution in certain market segments, particularly where market inefficiencies are more likely to exist, market valuations appear extended, or fund managers demonstrate a durable competitive advantage.

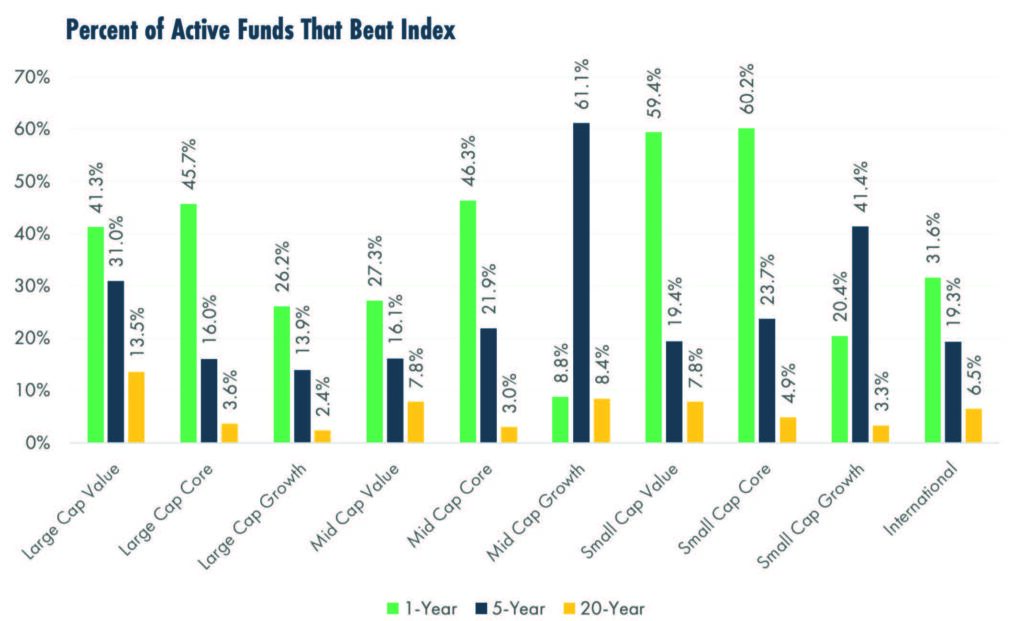

Both arguments have merit, but it is important to look at the nuances within market segments. The most recent SPIVA®, the S&P Indices Versus Active Scorecard, published in early 2023 using 20-year data as of December 31, 2022, calculated the percentage of actively managed equity funds that beat the comparable S&P Index by market category (e.g., U.S. Large-Cap Growth versus S&P 500 Growth Index, U.S. Small-Cap Value versus S&P SmallCap 600 Value Index, etc.). Below is a summary of some of the study’s findings.

As of December 31, 2022. All data except International is on an absolute return basis and does not account for fees that an investor may incur. See disclosures. Source: SPIVA U.S. Year-End 2022, Reports 1a and 6a (Published March 7, 2023)

While the results capture a static point-in-time, they offer interesting insights for the active versus passive debate. Over longer-term periods, active management has had less success beating the category benchmark compared to shorter time frames. The lower long-term success rates suggest that although it is not impossible to beat the benchmark, it is hard, with only a select few outperforming. Secondly, active management may be better suited in some market segments than in others. Over the trailing 20-year period, 13.5% of Large Cap Value managers outperformed the category benchmark. This compares favorably to Large Cap Growth funds where only 2.4% of active managers outperformed the benchmark. Finally, the data suggests that there is a greater chance of outperformance for active funds in the lower market capitalization and international asset classes, perhaps because these markets can be less efficient or less followed compared to US Large Cap stocks.

Taken together, the relatively low success rate of active funds highlights the importance of carefully reviewing the historical performance, fees, and investment strategy when selecting an active manager. An active manager should demonstrate a durable competitive advantage and a strong track record of either beating or producing better risk-reward metrics (e.g., a higher Sharpe ratio) than the benchmark to justify continued use instead of a passive fund. To provide the best chance to accomplish this, active managers typically have dedicated research analysts that leverage their expertise, experience, and research databases to locate mispricing within the market. Preferably, these analysts also utilize a “boots on the ground” approach where they tour prospective companies’ headquarters and have frequent discussions with senior management teams to augment their fundamental analysis. We regularly evaluate our preferred active managers’ performance, expenses, and adherence to their investment mandate, among other qualitative and quantitative measures, to maintain confidence that they provide value relative to their passive fund peers.

Despite the SPIVA® study and other statistics suggesting the odds strongly favor passive investing, there are some less frequently debated shortcomings of passive funds that prevent us from building portfolios entirely comprised of passive funds. For one, a passive fund manager must quickly, consistently, and accurately replicate the holdings of the index to ensure tracking error, or the difference in the fund’s return compared to the fund’s benchmark, remains as close to zero as possible. In most cases, this is a nonissue due to technology and algorithms that make these changes easily executable. However, this can be a challenge when a passive fund needs to replicate an international benchmark. For example, the fund might trade on U.S. exchanges, but the underlying stocks might trade on foreign exchanges with different market hours, potentially causing a mismatch between when an index is updated by its operator and when the passive fund manager can execute trades to realign the fund. Similarly, a passive fund that tracks a Small Cap index might have trouble fully replicating a change quickly due to a lack of trading volume in the underlying Small Cap stocks. In these cases, active fund managers may benefit from their ability to exercise discretion when trades are executed, allowing them to find more attractive opportunities to trade in or out of a stock. Additionally, when markets are experiencing strong, positive momentum, indexes weighted by market capitalization, and the passive funds that track them, can become significantly concentrated, which can reduce diversification benefits. As of June 30, 2023, the top 10 stocks in the Russell 1000, an index that tracks the largest 1,000 U.S companies by market capitalization, accounted for nearly 27% of the index, greater than the 24% reached at the height of the dot.com bubble3. Should one of these top 10 stocks report poor earnings or be the subject of a negative news headline, a decrease in its stock price could have an outsized effect on the index’s overall performance. Active managers can mitigate this risk by choosing to underweight a particular stock relative to the index or avoid it altogether if the company’s fundamentals or valuation warrant an exclusion.

In our opinion, the question of active versus passive investing is not about choosing one over the other. Rather, it is beneficial to integrate both active and passive funds in the context of a thoughtfully designed portfolio. Passively managed funds form the bedrock of a diversified portfolio, allowing investors to effectively gain market exposure (i.e., beta) at a low cost, particularly in relatively efficient market segments. At the same time, portfolios can benefit from incorporating thoroughly researched actively managed funds in asset classes that experience common shortcomings of passive funds and can benefit from market inefficiencies.

1 – The term “passive” may be a bit of a misnomer. Regardless of an investor’s desire to track a specific market segment, they must still decide which index to follow and which manager to use before ultimately concluding which fund to buy. For example, if an investor wants to invest in Large Cap U.S. stocks, they must decide which index to track. Some funds track the S&P 500 Index, others follow the Russell 1000 Index, while still others track the CRSP US Large Cap Index. Each of these indexes are constructed by index operators that utilize varying rules concerning inclusion, exclusion, and weightings. Suppose the investor decides they want to track the S&P 500. Now, they must decide which manager to use. The managers of the three most significant funds that track the S&P 500 are SPDR S&P 500 (SPY), iShares Core S&P 500 (IVV), and Vanguard 500 Index Fund (VOO). Thus, an investor must arguably make an “active” decision on which “passive” fund to use.

2 – Morningstar Direct (September 7, 2023)

3 – FactSet (July 5, 2023)

© 2023 Advisory services offered by Moneta Group Investment Advisors, LLC, (“MGIA”) an investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). MGIA is a wholly owned subsidiary of Moneta Group, LLC. Registration as an investment adviser does not imply a certain level of skill or training. The information contained herein is for informational purposes only, is not intended to be comprehensive or exclusive, and is based on materials deemed reliable, but the accuracy of which has not been verified.

Trademarks and copyrights of materials referenced herein are the property of their respective owners. Index returns reflect total return, assuming reinvestment of dividends and interest. The returns do not reflect the effect of taxes and/or fees that an investor would incur. Examples contained herein are for illustrative purposes only based on generic assumptions. Given the dynamic nature of the subject matter and the environment in which this communication was written, the information contained herein is subject to change. This is not an offer to sell or buy securities, nor does it represent any specific recommendation. You should consult with an appropriately credentialed professional before making any financial, investment, tax or legal decision. An index is an unmanaged portfolio of specified securities and does not reflect any initial or ongoing expenses nor can it be invested in directly. Past performance is not indicative of future returns. All investments are subject to a risk of loss. Diversification and strategic asset allocation do not assure profit or protect against loss in declining markets. These materials do not take into consideration your personal circumstances, financial or otherwise.